Miniature models of nurses from the Primitive era to the 1980s | These models were Dean Nancy Long’s idea and she had them made. They were used for career information when visiting schools. In 1972 when the uniforms changed from traditional to more modern trends, they created interest for prospective trainee nurses. Each model is held upright with a wire frame. Each miniature has an identity in Roman script, as well as information about each era of nurses. Models are 30cm in height and the maker details are unknown. They were made in the 1970s, beautifully designed, and used as promotional interest during career visits | Acquired by NDSN in 1989.

Primitive Woman

The first ‘nurse’ was the mother. The earliest human families were probably ‘matriarchal’ with the mother as centre of head. This was natural because men were the hunters and often strayed away from home for long periods in pursuit of their quarry. It was probably by the women collecting and throwing seeds around their dwellings that knowledge of how to grow grain for food and plants for medicine was first acquired.

Infectious disease invaded these primitive tribes and thinned their numbers and the sick were regarded as victims of superhuman power or witches. Out of this developed the medicine man or witch doctor.

Hygeia

As time went on and the treatment of disease became associated with religion, the medicine man was succeeded by the priest-physician.

The ancient Egyptians, Babylonians, Greeks, and Romans believed that the gods directed their physical welfare, as well as their spiritual welfare. Medicine was therefore held to be of divine origin. Temples were built to house the priest-physicians and priestesses who were of high social standing. At Epidaurus, in Greece, there stands the remains of the temple of Asklepios. It provided hostels, hospital wards, bath houses, gymnasia, outdoor theatres, library, residences for priests and attendants, and temples for sacrificial rites. Asklepios had two daughters, Hygeia, who symbolized health, and Panacea, the restorer of health. Hippocrates, one of the greatest physicians that ever lived, was born in 460 B.C. He laid the foundations of scientific medicine and his ideals of ethical conduct and practice are still used in the oath taken by students graduating from many medical schools today.

Fabiola

The Roman Aenius found its expression not in medicine, which was practiced mainly by Greek physicians brought to Rome as prisoners-of-war, but in the science of public hygiene. They also developed an organised medical system. Julius Caesar was the first statesman to

encourage the study of hygiene by recognising its teachers as professors of the arts with rights of citizenship. The women of Rome in pre-Christian times and up to the second century in the Christian era were very independent. For nearly 200 years it has been possible for them to

possess wealth and property and to be granted certain civic rights and privileges. They were free to come and go under the protection of the ‘Stola Matronalis’, a mantle which they donned after marriage. It was this free domain and independence that they had acquired under Roman law that enabled them to prepare themselves for responsibilities outside their

homes. Nursing the sick was one of these responsibilities. With the coming of Christianity the principles that Christ taught gradually reached Rome and many Roman women were converted to Christianity. Fabiola was the beautiful and idolised daughter of a great Roman family. After

an unhappy marriage, she became a Christian, renounced the world, and threw herself whole-heartedly into charitable work among the sick and poor.

Benedictine Monk

From the time of Christianity, nursing became truly continuous. Nursing duties were at this time not thought to be the vocation solely of women.

Hospitals were founded, which became part of the church or place of worship. These hospitals and monasteries, besides establishing a system for the care of the sick and poor, helped to restore and maintain a standard of learning and culture by providing a refuge for wandering scholars. In 529 an Italian Monk, named Benedict, laid the foundations

of a monastery. Much of the great work of Christianising Europe was accomplished by Benedictine Monks.

Abbess

The Monastic ideal of humility required early nuns to wear sensible dress and so the convent women spun the wool and made the cloth for their garments. No distinctive dress was at first required and, as Abbesses and Nuns were not wholly withdrawn from the world and were permitted to travel, their costume came to reflect the fashion of their time. Sometimes this led to extravagances. This type of apparel attracted criticism and led to the ultimate reform which ended in uniformity. The veil as an article of women’s dress has a long history. Its symbolism meant obedience, humility, and service. It was at one stage regarded as keeping evil

spirits away from a bride and then it distinguished her in her married state. Within the church, women veiled their heads and the length of the veil indicated their social position. Among religious orders, the veil of the young nun before taking vows was always white. As a symbol of service to mankind, the veil continues in the cap of the modern nurse.

Knight Hospitallers

When Jerusalem was captured by the Christians in 1099, the order of St. John of Jerusalem sprang at once into importance. At first, the knights undertook only charitable duties but between 1120 and 1160 they helped also to defend the holy city. The order consisted of both men and women and they nursed on a large scale. Their association with the highest orders of knighthood and chivalry gave the order prestige and influence which stimulated all future hospital organisations. The dames of the order were required to be of ‘noble birth’ and both the knights and ladies were pledged to the service of mankind. The emblem of the order, the eight-pointed white cross, is still worn by members of the St. John Ambulance.

Brigade.

Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul

In 1638, St. Vincent de Paul with the help of Mademoiselle de Gras, gathered together a number of young country women, mainly of the peasant class, and taught them simple nursing procedures which they performed in the homes of the sick. They worked in the home, the hospital, and on the battlefields. At first, the life of a sister of charity was a very hard one and her duties as a sick nurse were arduous and trying. Methods of alleviating pain were then unknown and she saw many painful and distressing sights. She was also constantly exposed to infection. After the death of St. Vincent in 1660, his successors

were not as enlightened as he, and the sisters were not allowed to share in the advances in medical science of the eighteenth century. In the 20th century, this was largely remedied and the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul may be found all over the world undertaking not only nursing, but teaching, and caring for the orphaned, the aged, the leper, and anyone who needs social service and friendship.

Mrs Sairey Gamp

Europe was faced with change. Exploration had opened up trade with Asia and America and ambitious men saw wealth and power in their exploitation. With the growth of towns, a new spirit invaded the church and the quality of monastic life was declining. In 1405 the church was estimated to have accumulated one-third of the wealth of England and its power surpassed that of the monarch. Henry VIII looked covetously upon

the enormous wealth of the monasteries and despite their long record of charitable, medical, and educational work, between 1536 and 1540 he dissolved them and took over most of their property. This left large numbers of helpless sick and poor to die. Thus began in England a dark period of nursing. Unlike other European countries where monastic nursing continued, England, as a result of the closing of the monasteries, possessed no nursing class, and for the next 300 years, nursing as a vocation and a charitable duty declined. Such hospitals as existed were grossly overcrowded and dirty and the sick beds came to hold more than one patient – sometimes as many as six. A shortage of suitable nursing staff led to the introduction of women of low character and moral standards. Charles Dickens satirised the nursing conditions of his time

in his description of Mrs. Sairey Gamp, thereby illustrating the depths to which the nurse had sunk.

Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale’s name became a legend in her lifetime and because of her achievements, she has been called the founder of modern nursing. Before Florence Nightingale went to the Crimean War, there was no such thing as professional nursing. When she died, nursing was established as a profession, organised and administered by women, offering educational opportunities and service to mankind on a scale never before thought possible. The conditions that Miss Nightingale found at Scutari were appalling. The wards of the Barrack Hospital were filthy, patients and beds verminous, medical and nursing equipment inadequate, and laundering nonexistent. In spite of the obstacles placed in her way by the military and medical leaders, she proceeded with calm resolution and confidence to plan and execute schemes for the care of the sick and wounded men which are now part of history. In gratitude for Miss Nightingale’s great achievements in the Crimea, the British people raised a fund to enable her to establish a school for the training of nurses.

The creation of the educated nurse, the essence of Miss Nightingale’s scheme of training, greatly affected practice and, conversely, medicine exercised a powerful influence on the development of nursing. At no time

since has nursing failed to keep pace with scientific progress in medicine.

Edith Cavell

The international nature of nursing is well-illustrated in the person of Edith Cavell whose death in 1915 aroused deep feelings in Europe and America. Miss Cavell trained in London and later became head of a nursing school in Brussels just before the German occupation in the First World War. When war broke out, she tended to wounded soldiers of both sides with equal devotion, but she was charged by the Germans with helping in the escape of allied soldiers to neutral territory. Pleading guilty, Edith Cavell was sentenced to death by the German Court Martial. To the British Chaplain who was with her in her last hours, she said, “Patriotism is not enough – I must have no hatred or bitterness for anyone.” She faced the firing squad with calmness and dignity. Her statue now stands at the Northern entrance to Trafalgar Square, London.

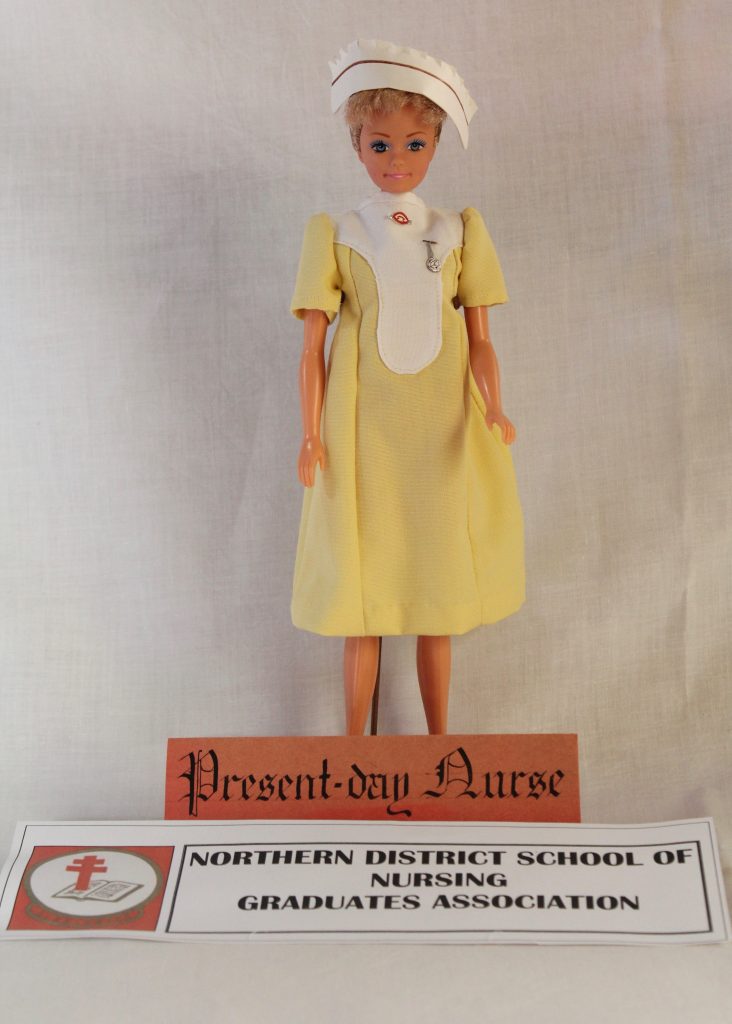

Present Day Nurse

The Northern District School of Nursing commenced in 1950. The Foundation Dean of the School was Nancy Winifred Long who continued in this role until 1974 when failing health forced her resignation. During those early years of the School, student nurses wore a simple blue dress with white shank buttons. This uniform was worn from School l (22/3/1950), through to School 7 (25/4/1951), when the “Modern Day Nurse” uniform was selected, complete with an apron and red cape. This uniform continued through to 1972 when designer Noeline

King was chosen to design a new uniform for student nurses. Through consultation with the affiliated hospitals the yellow and white colour combination was chosen and the designer uniform, complete with a matching yellow jacket, was first worn by School 80 (PTS 31/7/1972). From then on the distinctive uniforms became a feature on the wards and the student nurses were affectionately nick-named “yellow canaries“. This uniform continued to be worn until the forced closure

of Northern District School of Nursing in July 1989; as a direct result of the transfer of nursing education into Colleges of Advanced Education.

School 108 (PTS 4/8/1986), had the honour of being the final school through the Northern District School of Nursing and being the last “yellow canaries“.

Northern District School of Nursing Graduates Association Inc. (NDSNGA)

Northern District School of Nursing Graduates Association Inc. (NDSNGA)